Apothecary

See also, details of some individual Apothecaries.

Ancestors in British India often followed the profession of Apothecary (title changed in 1894 to Assistant Surgeon) and it is hoped that this article will help you to track yours down and learn more about how they lived and worked.

Overview

Definition

There are two apparent contradictions that researchers will face straight away. According to usual definitions, apothecary is an old fashioned word for a pharmacist, while surgeons perform surgery. In this context however, they are used for the same job at different times and in fact Apothecaries in the earlier period and Assistant Surgeons in the later were required to do both and much more besides.

Military or Civilian?

The second problem concerns whether they are Military or Civilian and the answer to this is almost always the former, although they could be posted as Civil Surgeons to hospitals and even jails. This article is about those Apothecaries who worked for the Government as part of the Military establishment. However, there were some Apothecaries who worked in a private capacity, for example as a Chemist and Druggist.[1] Details about these Apothecaries may be sought in the Commercial sections of Directories such as Thackers.

Crawford’s Roll of the Indian Medical Service

A further frequently asked question is why an Assistant Surgeon ancestor does not appear in Crawford’s Roll of the Indian Medical Service 1614-1930. Apothecaries as members of the Indian Subordinate Medical Department, rather than the superior Indian Medical Service, generally are not listed in Crawford, except for some entries relating to the Madras Presidency in the very early years, probably prior to the establishment of the Subordinate Medical Department. It should be noted that IMS used the title Assistant Surgeon for its lower ranks until 1873 and that the ISMD used the same title after 1894. Therefore if your Assistant Surgeon appears with that title before 1873, he should be in the IMS and will not be an Apothecary.

Medical personnel appointed to the IMS will almost always have been educated in the UK, even if they were born in India. They always held higher medical ranking. This London Gazette article set out the requirements for Assistant-Surgeons in the service of the East India Company in March 1856.

Conversely, however brilliant, the Indian born and educated men were trained in India and provided service in the ISMD, on lower pay scales. Some did rise in seniority, but would always be 'inferior' to their colleagues in the IMS. As the years went by, this perceived inferiority became an issue to be addressed. There are examples of men in the ISMD trained elsewhere, although these were in the minority. For example, The London Gazette Oct 17, 1919 lists under To be Senior Asst Surgeon with rank of Lieutenant: 1st class Asst Surgeons, 10th Feb 1919, Frederick William Mathews, L.R.C.P and S.I., L.M (Dub) ie Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians (London) and Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (LRCSI), coupled with a Licence in Midwifery.

British Library definition

The India Office Family History Search, in its Dictionary, gives the following description of Apothecary:

- "The title given to the various grades of warrant officer in the Indian Military Subordinate Medical Service. The rank of Apothecary was abolished in the Subordinate Medical Service in 1894 and replaced by that of Assistant Surgeon. Apothecaries in the Indian Army undertook general medical duties - by the early 19th century the word was used in the more general sense of medical practitioner as well as in its original meaning of pharmacist."

The word 'Service' is not quite accurate in the definition above and should be replaced by 'Department'. Surgeons trained in Great Britain, held covenanted positions in the Medical Departments of the Presidencies and later in the Indian Medical Service and were of officer rank in the Army. The European establishment of the Subordinate Medical Departments of the presidencies (with abbreviations such as Sub Medical Dept, Sub-Med Dept, S-Med Dept, SMD.) and of the later Indian Subordinate Medical Department (ISMD) consisted of the uncovenanted positions of Apothecaries and Stewards, Assistant Apothecaries and Assistant Stewards, together with those in training for these roles called Hospital or Medical Apprentices. The first four positions were of Warrant Officer rank,[2] but this rank did not apply to Hospital or Medical Apprentices. The members of the SMD were almost always locally born and recruited, although there were the odd exceptions.

The Early Years

Training

In Bengal, a formal scheme to train apothecaries commenced following a General Order dated June 15, 1812 by the Governor General which “approved a Plan submitted to him by the Medical Board, for the instruction of Boys from the Upper and Lower Orphan Schools and Free School, to serve as Compounders and Dressers, and ultimately as Apothecaries and Sub Assistant Surgeons in the Medical Department of this Presidency...The Medical Board shall select 24 Boys of 14 or 15 years of age, from the above Institutions, in the choice of whom the Governors of these schools are enjoined to afford every possible assistance.”[3]

The Upper Orphan School was the Military Orphan School for Officers’ Children and the Lower Orphan School was the Military Orphan School for the children of Warrant Officers and soldiers. Not all the children were orphans. The Free School was for children of non military fathers. The background of the boys from the Lower Orphan School was approximately 25% European and 75% Eurasian (or East Indian or from 1911 Anglo Indian), with a European soldier father and Indian or Eurasian mother. The percentage of Eurasians in the Upper Orphan School was higher, as orphans with European parents were returned to England, provided they had family there who could care for them.

Subordinate Medical Departments were also established in Madras in 1812, and a little later in Bombay.

The Madras journal of literature and science detailed the Madras Medical School (established 1835) in an 1838 article. Private Students, or persons not in the Public Service, were admitted from August 1838.[4]

Medical College training for Hospital Apprentices was introduced in 1847 in Bengal following the system that had previously been successfully introduced in Madras. "General Order 200" dated 15 June 1847 is about Apprenticeships in the Bengal Subordinate Medical Department. It sets out that candidates would sit an examination to become an apprentice. Those successful would serve for two years as an apprentice in the Hospital of a European Regiment or General Hospital. They then may be selected by the Medical Board for a studentship in the Medical College. They would then attend a two year course of study comprising Anatomy, Dissection, Materia Medica, Pharmaceutical Chemistry, the practice of Medicine and Surgery and more especially clinical instruction in connection with the last two branches. At the end of the two years they were to undergo an examination. If successful they were to be drafted to European Regiments or to the General Hospital, there to wait their turn for promotion as Assistant Apothecaries or Assistant Stewards. Promotion to Apothecary was also to be by examination.[5]

However, when the Indian Mutiny occurred (1857), the classes at the Medical College for Hospital Apprentices were broken up. Due to the shortage of medical personnel, and the demand for them in the regiments, this situation continued for over ten years [in Bengal]. A decision was made in July 1868 to recommence classes for the Hospital Apprentices at the Medical Schools.[6]

The Bombay Medical Board issued new Rules for training Medical Apprentices dated 2nd April 1851. They were similar to Bengal, but required three years of Medical College prior to becoming an Assistant Apothecary with progression to Steward, then Apothecary.[7]

It is interesting to note that from 1869 until the founding of the King Edward VII College of Medicine in Singapore, apprentice Apothecaries were also recruited from schools in that region and trained in the Madras Medical College.[8]

Formal training for the Subordinate Medical Department, Hyderabad commenced when the Bolarum Medical School was established in 1839 to “qualify India-born lads for all the subordinate medical grades and duties of the [Nizam’s] Army”. On graduation, they were qualified to be 2nd Dressers.[9] In 1846 the Bolarum Medical School was closed, as it was no longer needed, and the Hyderabad Medical School at Chuddergha(u)t, (now the Osmania Medical College) was then established.[10] In 1868, the Times of India reported that “the assistant apothecaries of the Hyderabad Contingent have all been promoted to apothecaries”... “the designation they now bear (assistant apothecary) was allowed them by Government not many years ago”.[11] The correspondence refers to the training in the Bolarum Medical School. It is unclear whether all the apothecaries referred to were trained in the period 1839-1846. It seems more likely the Hyderabad Medical School continued this training.

Promotion

In 1841, John McCosh stated, in respect of the situation in Bengal:

“They enter the service as hospital-apprentices, on the pay of 33 rupees a month; after ten years service they are promoted either to assistant-apothecaries or assistant-stewards, on an allowance of 70 rupees; and, after about nine years in that grade, they are promoted to apothecaries with the pay of 140 rupees a month, or stewards with the pay of 120 rupees. To every European regiment, whether Royal or Company's, there is an apothecary and a steward attached, with each his assistant.”[12]

In earlier years the assistant apothecaries were promoted much more quickly. William Hannah was promoted from Assistant Apothecary to Apothecary in December 1824[13] when he was about 22 years old, and there is an 1818 reference to Apprentice Henry Anderson who was appointed directly from Apprentice to Apothecary.[14]

However, it seems the situation did change and that promotion became much slower. When William Hannah became an apothecary in December 1824, ten were appointed assistant apothecaries. Of these, three became apothecaries in January 1834, almost exactly nine years later.[15] So it does seem that if an apothecary was appointed from 1834 onwards he would probably be aged in his thirties at date of appointment which may help to indicate a date of birth (if not otherwise known).

Extra Assistant Apothecary

A few cases have been heard of where appointments have been made to the rank of Extra Assistant Apothecary, in the Bengal SMD. These appear to have been made following the Indian Mutiny when demands for trained personnel would have been great. In one case the Extra Assistant Apothecary appears to have been working prior to the appointment in a private capacity in Calcutta as an apothecary, perhaps as a chemist and druggist. His training and birth details are unknown. He unfortunately died soon after. In another case, the Extra Assistant Apothecary was born and trained in Britain. Thomas Baron appears in the list of Extra Assistant Apothecaries in the 1861 edition of the New Calcutta Directory, the only known list, as appointed 29 April 1858. Born in Manchester in January 1837, the son of a Chemist and Druggist, he appears in the England 1851 census as a scholar aged 14. In 1858 he would have been 21. Family word of mouth says he went to India as some sort of a Medical Officer. Possibly he had been apprenticed to his father. Interestingly, he subsequently appears in the lists of Hospital Apprentices with appointment date 10 October 1861, indicating that at least in his case, his appointment in 1858 had not been permanent. (He then appears to have sat all the required examinations before receiving an appointment as an Assistant Apothecary).

The London Lancet refered to the grievances of the Hospital Apprentices “to see a number of strangers admitted into the service with the rank of assistant apothecary, who never served as apprentice in it, in preference to the apprentices, of whom it is said that upwards of forty passed members await promotion. Undoubtedly, in periods of emergency, rules may be transgressed when necessary to secure the efficiency of the service, and it may be desirable, at a particular moment, to secure the aid of skilled civilians to whom adequate rank and pay must at once be offered ...”[16]

There were similar appointments to the rank of Extra Assistant Steward, who also appear in the 1861 New Calcutta Directory list. See also the individual Apothecaries page.

Duties

The following 1855 description of the duties of apothecaries and stewards, and training, is in "The Medical Services of the British Army" in The British and Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review:[17]

- “An invaluable appendage of the Indian army is the subordinate medical department attached to it. This, in Bengal, consists of the European establishment, and of a special class of subordinate agency for the native army, and for duty in civil hospitals appropriated to natives.

- The European establishment consists of apothecaries, assistant-apothecaries, apprentices, stewards, and assistant-stewards. The apothecaries are charged with the preparation and administration of medicines, the care of wounds, accidents, and injuries, during the intervals of the visits of the surgeons, the admission of patients, and, in fact, are the general assistants of the medical officers in the performance of their professional duties in the field, in garrison, and in all the circumstances in which the troops are employed. It would be impossible to exaggerate the usefulness and importance of this excellent class of public servants. As a body, they are a credit to the service, and are of more real use, from their careful professional training, than any body of nurses could possibly be, to the sick and wounded.

- They are usually the sons of soldiers, educated in the regimental schools, or in the Military Orphan School. They are admitted to the service after examination by special committees of medical officers—a concours upon a small scale—and after doing duty in regimental hospitals for two years, are (if in Bengal) transferred to the medical college in Calcutta tor two additional years of training. There they are under strict military control; are instructed in anatomy, materia medica, medicine, and surgery; are carefully trained in hospital duties as clinical clerks; and, after undergoing a tolerably strict examination—in somе particulars more severe than that of the College of Surgeons of England—are reported qualified. If they fail, are idle and insubordinate, and otherwise misconduct themselves, they are removed from the army, and forfeit all the advantages of their previous service.

- In the recent Burmese campaign, and in the late Punjaub war, they were found most efficient field-assistants; and we are able, from personal knowledge, to state that some of them are more efficient members of the profession, and generally better informed, than some assistant-surgeons with whom we have come in contact, armed with degrees and diplomas from British schools of old and great pretensions. (Note: Remember that at this date assistant surgeon was an IMS title).

- The stewards and their assistants are charged with all the details relating to the food, clothing, and similar interior economy of military hospitals. Both classes aid the surgeon in the preparation of official reports and statements."

Change of Duties

There is a British Library catalogue entry IOR/F/4/661/18358 Mar 1821 which appears to be in respect of Bengal: Appointment of J.T. Hodgson as Veterinary Surgeon to the Governor General's Body Guard - he is to select and train eight Assistant Apothecaries as Veterinary Surgeons for the Light Cavalry Regiments.

Further reading

- "The Loodianah Field Hospital, With Remarks On The State of The Army Medical Department in India" by John Murray, M.D., Field Surgeon. page 158, Medical Times (1849) - an article about a Field Hospital after battle in 1846 including medical details, with the slightly wounded carried out on elephants.

- "Field Arrangements in India" in Army Hygiene by Charles Alexander Gordon (1866) page 255 - an article about the logistics of a Field Hospital, including the number of camels required for the apothecaries and stewards.

- The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal By Massachusetts Medical Society, New England Surgical Society Published 1842, page 17 - the numbers of staff in the Medical Department in India including number of apothecaries, approx 1842.

- The Cambridge (UK) Centre of South Asian Studies, in its Archive Collection, has the Winn Papers which contain information about James Winn who joined the East India Company in the Bengal Establishment in 1842, aged 13. He served as an apothecary at various stations including Lahore, Multan, Dinapore, Dum Dum, Allahabad, Calcutta, Chunar. He was invalided out of the service at Meerut in July 1884. (WINN 1/1 Testimonials, statements of service, etc in connection with James Winn's work as an apothecary in the service of the Bengal Establishment, 1842-1884, 45 items)

- The Wellcome Library, London has the article "Apothecaries and Hospital Assistants in Colonial India" by Harkishan Singh in the Pharmaceutical Historian Vol. 32, no. 1 (Mar. 2002)

The Situation by the 1870s

General Order 550 of 1868 introduced some changes to the organisation of the Subordinate Medical Department and a revised and enhanced scale of pay and pensions. This appears to have been re-released in March 1869, no 1798 20 March 1868 ( should be 1869?) to state it also applied to Apothecaries and Assistant Apothecaries employed in the Civil Department. The main change was that the grade of Hospital Steward in the Bengal and Bombay Presidencies was abolished and replaced by the system in place in the Madras Presidency, where the purveying duties were undertaken by the Commissariat Department through Hospital Purveyors. The grade of second Apothecary at Madras was also abolished, the members being merged in that of Apothecary. Refer to the “Notes” below for full details.[18] Some of the revised scales are set out in the following books by William Cornish.

The following information is from a book published in 1870 and relates to Madras. However, it would be expected that conditions would be much the same throughout India. By this time the course at Medical College (at least in Madras and Bombay) had been extended to three years, but there was still a two year period before college, when there were examinations every six months.

Pupils and Apprentices of East Indian or European parentage were prevented from marrying until they had passed through Medical College (Page 85)

The examination for promotion from Assistant Apothecary to Apothecary consisted of Anatomy, Surgery, Materia Medica, Pharmacy, Practice of Medicine, Midwifery and Vaccination (page 99)

One tenth of the number of Apothecaries were to be Senior Apothecaries (page 86)

A salary scale is set out on page 126. In addition, the members of the Subordinate Medical Department received free quarters and at least the Hospital Apprentices received food.

- Per month the rates in rupees were:

When in College: First year 20, second year 25, third year 30 Passed Hospital Apprentice: 50 Assistant Apothecary: Under 5 yrs service 75, over 5 yrs service 100 Apothecary: Under 5yrs service 150, over 5yrs service 200 Senior Apothecary: 400

They were also allowed a Field Allowance of Rs 30 per mensem (month) when marching or in the field. Also a staff or employed allowance when senior with, or in subordinate medical charge of, the hospital of a British Regiment or detachment of British Troops, or a Battery of Artillery, or a Depot or Sanitarium or when attached to a General Hospital or Medical Store Depot. Hospital Assistants were in a different stream, serving in Native Regiments and Hospitals.

The book is A Code of Medical and Sanitary Regulations for the Guidance of Medical Officers serving in the Madras Presidency (2 Volumes) by William Robert Cornish (1870). They are available to read online on the National Library of Scotland’s website Medical History of British India. The above references are in Volume 1

Gary Bateman has advised that “Civil Apothecary was an intermediate class between Civil Assistant Surgeon and Civil Hospital Assistant. It was only in the Madras Presidency and started in 1875 but was abolished in 1884. There were five grades, Rs 50, 75, 100, 125, & 150 with an additional Rs50 charge allowance.”

Some apothecaries working in hospitals also had some private patients, as this article (Madras Quarterly Journal of Medical Science 1863 v7) details.

Madras 1863. Promotion of three Senior Apothecaries to Honorary Assistant Surgeons, without, however, any additional allowance by virtue of the honorary rank. This is contrasted unfavourably with the situation in Bengal, where Apothecaries had been promoted to the rank and position of Commissioned Officers. Madras Quarterly Journal of Medical Science 1863 Volume 6, page 465

The Later Period

Towards the end of the 19th century and into the 20th, Apothecaries and Assistant Surgeons continued to perform their duties but increasingly it seems that they were “in Civil Employ”.

However, the essentially military status of Assistant Surgeons is made clear in a document dated 28/2/1931 by Lt Col HAJ Gidney, IMS retired.

This appears in 'Collection 116/50 Improvements in pay and prospects of military assistant surgeons of Indian Subordinate Medical Department, including removal of the word "Subordinate". IOR/L/MIL/7/5321 1914-1934', which is discussed in more detail under The Question of Status.

Gidney writes:

- “The IMD, previously known as the Apothecary class and until recently called the ISMD has been in existence for about 100 years and, although mainly recruited from the Anglo Indian and Domiciled European community, it includes many non-domiciled Europeans..... It has a record of military service in all parts of the Empire with a high percentage of military honours gained on almost every battlefield. Its members are recruited in precisely the same manner as every other British soldier: they take the same oath and are primarily intended for exclusive duty in the British army and are attached to British Military Hospitals: they undergo a five years' course of medical training at the Medical Colleges of Madras and Calcutta and attain a high professional standard. About 80 of a cadre of 600 possess a British medical qualification.

- “In India they are recognised as fully qualified medical men and are registered as medical practitioners under the Medical Act. Like the IMD, RE and other Departments of the Indian Army, the IMD is recruited “over strength”, the surplus officers being used by various Provincial Governments in civil capacities and are recognised, as are the IMS Civil Surgeons, as the war reserve of the Army, and the army has first call on their services.”

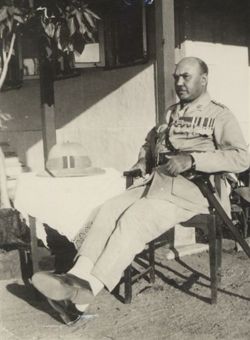

An example of an Assistant Surgeon with a distinguished military career is Major Hector Alfred Richardson (1875 – 1957).. Born in Ellichpur, he worked at the J.J. Hospital in Bombay in the 1890s for a couple of years, presumably having trained in the adjacent Grant Medical College, and then joined the Indian Medical Department, Army Service, and was shipped out to the Boer War in South Africa, Ladysmith Relief in the 1898/99. Returning to India, his subsequent postings included: 1904 Meerut; 1906 Deolali; 1908 Calcutta; 1911 Agra Cantt.; 1912 Bhusaval; 1914-1919 Lahore; 1923 Jhansi; 1929 Meerut & Ajmer; 1931 - 1938 Jhansi; 1941 - 1942 Mhow; 1946 Jhansi.

Thus we can see that ISMD employees, could, with application, rise to the rank of Major, but in many cases there was growing dissatisfaction with pay and status. See the following entries on Civil Surgeons, who, it seems, led demanding and frustrating lives although the pay was better than in the Military and the range of professional duties greater.

- The Indian Medical Gazette 1868 page 272

- History of Medicine in India by Chittabrata Palit, page 168 (Limited view)

Tracing a Surgeon

Thacker's

Thacker's Bengal Directory, published from 1864, was in 1885 renamed Thacker's Indian Directory and covered the whole of British India. Volumes for most years are available in the Asian and African Studies Reading Room at the British Library and the 1895 edition is available to purchase as a CD. It is a useful source for tracing Assistant Surgeons of both Military and Civil persuasions.

Thus one can find, for example, Assistant Surgeon Patrick McCarthy in Thacker’s:

- 1892-5 - Assistant Surgeon, doing duty at the hospital at Bareilly, North West Provinces

- 1903 - Assistant Civil Surgeon and Superintendent of Jail, Lower Chindwin, Burma

Indian Army Lists

Another invaluable source is the Indian Army Lists, like Thacker’s, available at the British Library. This B.L. webpage Indian Medical Service advises that members of the Subordinate Medical Department are recorded in the published army lists, L/MIL/17/2-4, Bengal from 1819, Madras from 1829, Bombay from 1832. (The catalogue entries are: Bengal Army IOR/L/MIL/17/2 1791-1903 Madras Army IOR/L/MIL/17/3 1787-1904 Bombay Army IOR/L/MIL/17/4 1794-1913). From 1889 to 1947, all members of the Subordinate Medical Department with the rank of warrant officer or above are recorded in the published Indian Army List in the Reading Room (Ref:OIR355.33). However, according to this India List post the L/MIL/17 Army Lists in the early years may not routinely include lists of Apothecaries. Quoting from Baxter’s Guide (Biographical Sources in the India Office Records), the post also advises that "Dates of Birth of Apothecaries are given in the lists from Oct. 1884".

Names may be searched from the Indian Army and Civil Service List 1873 in Find My Past’s Migration category. It is not stated whether original data is available or whether this is a transcription. A transcript of the January 1912 edition is available online via Ancestry.com

The LDS(Mormon) Library catalogue has the following entry for India Office Army Lists 1886-1940 available on fiche. Note that it is not known whether the LDS Lists are exactly the same as the Lists at the British Library Reading Room.

Here again are some sample extracts:

- July 1888 – Listed under Subordinate Medical Department, Sub Assistant Apothecaries - McCarthy P. Date of present rank 1 Mar 88.

- Apr 1901 - Asst surgeon 2nd class Ranking as Conductor, McCarthy, Patrick (105) = Qualification Burmese Lower Standard) B (for Bengal) DoB 19 Feb 1868, d of warrant rank 1 Mar 88, d of present rank 1 Mar 00. At Monywa.

- Oct 1910 - Medical Warrant Officer, Indian Subordinate Medical Department, Assistant Surgeon First Class ranking as Conductor. Date of Warrant Rank 1/3/1888, date of present rank 1/3/07, Civil and Jail, Hensada (Assistant Surgeons seconded for Civil Employ)

- Oct 1918 - Senior Asst Surgeon with honorary rank of Major, Date of 1st command 26 Dec 10, date of present rank 25/12/1917. Civil and Jail Akyab.

Service Histories

Once the whereabouts of your ancestor in a given year has been established, a useful next step is the IOR V/12 Service Histories. The necessary volumes can be found using Access to Archives. Look at IOR/V/12 and chose one or more relevant volumes. There are an alarming 434 volumes of Service Histories, and as well as whole sequences of volumes for the 3 Presidencies, there are more sequences for India, Assam, Bihar & Orissa, United Provinces, Punjab, North West Frontier, Central Provinces, Burma and Hyderabad! The earliest date from 1879 and the latest 1948, though dates for particular regions vary. The later you can get in your Assistant Surgeon’s career the better, as the information appears to be cumulative. The documents themselves are held at the British Library.

In addition to the postings, the Service Histories also contain other details relating to leave and training.

Hence the following extracts from Histories of Service in Burma - Medical Department IOR/V/12/406 for 1921 relating to Patrick McCarthy:

- Sandoway – Civil Surgeon - 28 Oct 1899

- Leave on medical certificate in India from 15th and out of India for 5 months and 11 days from 17 August 1900, the date of being struck off duty being 15 Aug 1900.

- Henzada - CS – 26 May 1909

- On deputation to Kasauli for training in Clinical Bacteriology and Technique from 25 Feb to 30 Mar 1912

- Henzada - CS – 6 Apr 1912

- On deputation to Calcutta for Royal Commission from 7 Jan 1914

Interestingly, by the time these records appear in 1921, this Assistant Surgeon is listed as IMD and not ISMD. The word “subordinate” was finally dropped in 1919 – this was the year it no longer appeared in The London Gazette. The deputation to Calcutta in 1914 was in pursuit of this aim, amongst others.

Thelma Cramb (nee Ferguson) has advised “As the daughter of an Assistant Surgeon I know how often they were transferred from one station to another - I was born in Dagshai (Simla Hills) in 1928 - my sister b. 1926 in Kasauli - another in 1924 in Bareilly - and another in 1922 in Chowbutia (Naini Tal I think !!) Happy days spent in Poona with other I.M.D. families.”

Assistant Surgeons and Superintendents of Jails

The employment of Assistant Surgeons as Jail Superintendents seems curious, but was the usual practice.

Reports on Jails, Hospitals, Public Health Departments and much more can be found in the IOR/V/24 series. As with the Service Histories they are searchable via Access to Archives site and available to view at the British Library.

See Superintendent of Jails for some details of daily life.

Records - The Question of Status

Collection 116/48

Collection 116/48 Issue of new Royal Warrant for promotion of assistant surgeons and sub-assistant surgeons. IOR/L/MIL/7/5319 1910-1933

This is a bundle of documents relating to honorary commissions, and includes the following Royal Warrant:

- “As of 1911, Senior Assistant Surgeons may be given the honorary rank of Lieutenant, Captain and Major. Promotion to the grade of Senior Assistant Surgeons with honorary rank of Major shall not ordinarily be made until after 15 years service in the Commissioned grade. Senior Assistant Surgeons shall enjoy the precedence and other advantages attaching to their honorary military rank.” Given at our court at Balmoral this 26th day of September 1911.

Some of the documents relate to LAH Clerke who was promoted on special merit before this warrant went through, being mentioned in the London Gazette 4 Jan 1911. At that time the royal warrant of 1894 still in force, hence proposal for a revision.

Collection 116/52

Collection 116/52 Recognition by General Medical Council of certain Indian degrees, including Licentiate in Medicine and Surgery of University of Madras. IOR/L/MIL/7/5323 1915-1916

This is an interesting collection of documents and correspondence. The hope had been that qualifications such as the LMS (Licentiate in Medicine and Surgery) would be recognised by the General Medical Council, and that at the end of 5 years in the ISMD, Assistant Surgeons would be able to study for further qualifications that would put them on an equal footing with their IMS colleagues. (Click here for a document, Chapter 11 from an unnamed book, which sets out the requirements for a medical qualification from the Indian universities.)

The outcome was to defer the adoption of the system of nomination for admission into the medical colleges for Assistant Surgeon branch of the ISMD. Presumably the decision was not taken at this time as it was the middle of the First World War and there were more pressing matters to hand - during this time many Civil Surgeons served for a time with the Military - but it would seem that the ISMD was put on a more equitable footing shortly thereafter.

It is clear from other documents in this collection that the ISMD had numerous grievances and that they were prepared to voice them:

- Rates of pay for 1915 are given, not vastly different from those given above for 1870:

4th class Assistant Surgeon ranking as sub conductor 100 rupees per month 3rd class 150 rpm 2nd class ranking as conductor 200 rpm 1st class 250 rpm Senior Assistant Surgeon with honorary rank of Lieutenant 350 rpm Senior with honorary rank of Captain or Major 450 rpm

- A letter dated 1907, says that the ISMD is no longer a desirable field for employment for young men. The pay is poor, particularly in junior grades: this and the 4 year course of professional study makes it difficult to recruit suitable men. There is a need to improve pay and prospects - an Assistant Surgeon has to serve for 19 years before promotion to 1st class. It was proposed to reduce this to 17 years, and introduce more “perks” relating to horse allowance, furlough pay etc.

- Correspondence with the General Council for Medical Education and Registration in London in which they point out that granting of qualifications is their remit and are entitled to refuse - they refused to acknowledge qualifications of State Medical Faculty of Bengal.

- In 1914, 18 Military Assistant Surgeons sent memorials to His Majesty’s Secretary of State praying for certain improvements in the pay, status and prospects of the ISMD – among them was Senior Assistant Surgeon AW Truter, who wrote a lengthy letter, including the following:

- “Your memorialist submits that the present designation, viz Indian Subordinate Medical Department, casts an undeserved slur on its members inasmuch as no Government Department of similar standing is designated “subordinate”, nor is the word “subordinate” borne by any department of the British or Indian Army... your memorialist would therefore crave your lordships indulgence in this respect and beg for the removal of a word so obnoxious as “subordinate” from his designation”

- This collection also includes a copy of the entrance exam to the ISMD in 1912. There are sections on English Composition, (eg write an essay on punctuality), Mathematics (including algebra), History and Geography (both Indian and UK based - candidates had to answer some of each.)

Collection 116/50

Collection 116/50 Improvements in pay and prospects of military assistant surgeons of Indian Subordinate Medical Department, including removal of the word "Subordinate". IOR/L/MIL/7/5321 1914-1934

This is another interesting collection that repeatedly underlines the problems of status experienced by the Assistant Surgeons.

The first document, dated 12 Feb 1914 to the Secretary of State India, is a submission for Your Lordship's consideration of a memorial submitted by Military Assistant Surgeons of the Indian Medical Department, praying for improvement of their pay and prospects.

It is proposed that the preliminary course of study be increased from 4 to 5 years, a 6 month probationary period and study leave of 1 month for every year's service.

Memo to the President of the Medical Board dated 20 Mar 1914, signed H Charles, states that “The Military Assistant Surgeon, when on Military duty, serves only with British soldiers and it is quite impossible for disciplinary reasons to replace him with an Indian however well qualified. He is absolutely essential to the Station Hospitals of India.” There is concern that the current 4 year course is insufficient and that the General Medical Council does not recognise the resulting qualification. Charles is particularly galled that “the Indian Assistant Surgeon who goes through a five year course despises the Military Assistant Surgeon”, adding: “I taught these men for 20 years and I know their importance.”

These proposals are duly put forward, although a request for an increase in pay is deferred.

Another memo to the Secretary of State in July 1914 asks for the removal of the word 'subordinate'. There is general agreement in principal, but a decision must await the report of the Public Services Commission.

The Gazette of India, Jan 2 1915, implements pay increase, promotion, study leave etc and the 5 year course.

“The standard of preliminary education of candidates for Admission into Medical colleges shall be raised to, or be equivalent to that required by the General Medical Council of Great Britain: and the present course of professional study shall be extended from four to five years.” Also the probationary period is agreed, as is 7 years service before discharge can be claimed.

In 1918 petitioners are still praying that the word 'subordinate' be deleted, and on 10 May 1918 a handwritten military dispatch to the government of India, printed on August 9 1918 states that the writer is “of the opinion that the designation “subordinate” can be abolished at once without prejudging any of the other recommendations of the Public Services Commission and I request that this be done.”

A memo dated 14 Mar 1921 sums up qualifications held by Military Assistant Surgeons at that time:

658 hold diplomas granted after examination held by the Director General of the Indian Medical Service 20 are Licentiates of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Bombay 2 are Licentiates of the State Medical Facility, Bengal 35 are Licentiates of the Board of Examiners Madras 11 hold qualifications registerable in England.

Civil assistant surgeons are usually graduates or licentiates in medicine of the medical colleges in Madras, Calcutta, Bombay, Lahore and Lucknow or Members of the Provincial Medical Faculties.

A document dated 21 Mar 1921 gives the rates of pay from 1920:

1-7 years service 200 rupees per month 8-12 years 275 rpm 13-17 years 350 rpm 18-20 years 400 rpm 21 years and over 450 rpm Lieutenant 500 rmp Captain 650 rpm Major 700 rpm

Further documents continue to highlight the problem of pay. Indeed Gidney’s defence of the IMD on February 28 1931 is written because IMD promotions and pay had been in line with those of other army departments, but recently had fallen behind. Other departments received a pay rise in 1927 while the IMD had to wait until 1929 and these payments were only sanctioned for those in military employ, those in civil employ being overlooked. This is why he was making it clear that however individual members of the IMD might be currently employed, they were still army men.

Other records

The reform of the ISMD is covered in more detail in the following Collections, which, to date, have not been perused by the authors:

Collection 116/8 Senior apothecaries no longer to be styled as warrant officers. IOR/L/MIL/7/5278 1886

Collection 116/13 Royal Warrant for grant of commissions to senior apothecaries. IOR/L/MIL/7/5283 1890

Collection 116/15 Names of senior apothecaries granted commissions under Royal Warrant. IOR/L/MIL/7/5286 1890

Collection 116/22 Apothecary branch: changes in rank and designation of members IOR/L/MIL/7/5293 1893-1894

The End of the IMD

The Indian Medical Department effectively ended as a separate entity on April 3rd 1943 when it was amalgamated with the Indian Medical Service and the Indian Hospital Corps. In this form, it still exists today.

Listings of Apothecaries

FIBIS resources

The FIBIS database has a listing of Apothecaries Serving in Bengal 1862, which contains Apothecaries, Assistant Apothecaries, Stewards and also Veterinary Surgeons and Riding Masters.

Other sources

Refer to the sections Thackers's and Indian Army Lists above

There is a British Library Catalogue entry IOR/F/4/1338/53155 Jan 1829-Oct 1831: Institution of a fund for the families of Medical Warrant Officers in the Madras Presidency (includes a list of Medical Warrant Officers ie Apothecaries, Second Apothecaries and Assistant Apothecaries, dated 9 Nov 1829, with notes on marital status, number of children etc. pp 35-45).

Some Directories contain lists of Apothecaries and Stewards, Assistant Apothecaries and Assistant Stewards, which contain details as to when they obtained their grading and where they were currently serving. The list, in a section headed Subordinate Medical Department is usually found at the end of the Military List, following a Medical Department List. Occasionally the apothecaries are found in lists where the heading is Warrant Officers. In a few volumes Hospital Apprentices are also included, or Passed Medical Apprentices in Madras. Even if there is no specific list, the apothecary’s name may appear in the Alphabetical List of Residents, particularly for the Mofussil.

Preceding the Apothecaries listings there are listings of the Surgeons and Assistant Surgeons in the Medical Department which will be of relevance if your ancestor was an Assistant Surgeon up until 1873.

Currently (May 2010) there are only eight known lists online:

- 1838 Bengal Directory, page 245

- The Bengal and Agra Directory and Half Yearly Register for the year 1843 is available to read online on the Digital Library of India website. Note some pages appear to be missing. The contents page is computer page 8, Apothecaries etc computer page 295.

- The Bengal and Agra Directory and Annual Register for 1848 is available to read online on the Digital Library of India website. The contents page is computer page 8, Apothecaries etc computer page 190.

Madras Quarterly Journal Of Medical Science (search within these volumes for ”warrant officers” or more generally for “medical warrant officers”):

- Madras at 1 October 1860 (Page 17 of appendix at end of book)

- Madras at 1 April 1861 (Page 17 of appendix)

- Madras at 1 October 1861 (Page 17 of appendix)

- Madras at 1 April 1862 (page 16 of appendix)

- Madras at 1 April 1863 (Page 19 of appendix)

For Bengal, the following have also been noted to contain lists. There may well be others.

- Scott and Co Bengal Directory and Register for 1844

- New Calcutta Directory 1857-1862, but excluding 1860. Hospital Apprentices, “Extra Assistant Apothecaries” and "Extra Assistant Stewards" are included in 1861.

- Thacker’s Bengal Directory 1864-1868. These volumes include Hospital Apprentices.

Ian Poyntz's website has information on the holdings of Directories in many libraries around the world, including the British Library. If you have access to any of these volumes you may find additional lists of Apothecaries, or entries in the alphabetical list of residents, entries under the Mofussil Listing, or entries in the births, marriages or deaths sections. Quoting from Baxter’s Guide, this India List post advises that "Lists of Apothecaries appear in Directories: Bengal, from 1815; Madras from 1862; Bombay, from 1832."

You can also try searching in Directories and Journals available online for additional lists of apothecaries which may be available in the future, and also for birth, marriage and death entries, and entries relating to postings and promotion.

In addition The London Gazette is a good source of information for promotions.

Crawford’s Roll of the Indian Medical Service 1614-1930 lists Apothecaries in the Madras Presidency although not the other Presidencies. The book is available as a LDS microfilm, with this library catalogue entry

There are mentions of students (Hospital Apprentices) in the Annual Report of the Madras Medical College. The British Library has reports from 1853 to 1887, missing 1854/1855. However, the 1854/55 report is in Appendix L of the report on Public Instruction in the Madras Presidency for 1854/55. Oxford University Bodleian Library also has a broken range of volumes to 1887. The following years are available online ( mainly Google Books):

- 1855-56, 1856-57, 1859-1860, 1860-61, 1861-1862, 1864-1865, 1866-67, 1867-68, 1868-69, 1871-72 Archive,org

General Orders

Details about the postings of Apothecaries appear in the Bengal General Orders by the Commander-in-Chief. The British Library reference is: Bengal General Orders by the Commander-in-Chief/General Orders by the Commander-in-Chief India IOR/L/MIL/17/2/269-352 1820-1903. Annual indexes appear 1833-1835, 1837-1838 and from 1850.

It is not known whether details of postings also appear in the Madras and Bombay General Orders. However the equivalent British Library references are:

Madras General Orders by the Commander-in -Chief IOR/L/MIL/17/2/412-456 1818-1895 There are annual indexes from 1845.

Bombay General Orders by the Commander-in-Chief IOR/L/MIL/17/4/467-501 1860-1895. There are annual indexes from 1868.

Other

This India List post advises that two Apothecaries and a Hospital Steward were found on a list of pensioners in the Bombay Muster records for 1857.

Notes

- ↑ The Wellcome Library, London has the article "European Pharmacies in Colonial India" by Harkishan Singh in the Pharmceutical Historian, Vol. 31, no. 4 (Dec. 2001).

- ↑ See Madras Quarterly Journal of Medical Science 1863 v. 7 (Google Books)

- ↑ The order as copied here was reported in the Calcutta Gazette dated Thursday, July 2, 1812 (Vol LVII, No 1479)

- ↑ Report on the medical topography and statistics of the Presidency Division of the Madras army, Thorpe, 1842

- ↑ This Order is in a book called General Report on Public Instruction in the Lower Provinces of the Bengal Presidency for 1847-1848, Appendix E, no. XI, page clxvi. Full Order, Further background information.

- ↑ Indian Medical Gazette page 158, July 1868

- ↑ Report of the Board of Education, Bombay January 1, 1850 to April 30, 1851 (Published 1851), pp235-246.

- ↑ Full details are given in "The Founding of the Medical School in Singapore in 1905" by YK Lee. There is further mention in “The early history of pharmacy in Singapore” by YK Lee Singapore Medical Journal 2006 May;47(5):436-43.

- ↑ “An Account of the Medical School at Bolarum” from The Madras Quarterly Medical Journal Volume 1 1839

- ↑ "How it all began", Osmania Medical College Alumni Association website.

- ↑ Correspondence in the Times of India dated 11 March 1868 and 18 March 1868

- ↑ Medical Advice to the Indian Stranger by John McCosh (1841) p5

- ↑ The Oriental Herald and Colonial Review Volume V, April to June 1825, page 530

- ↑ Asiatic Journal Vol VI, June-December 1818

- ↑ Of the others, one became a steward in September 1826, one was on the invalid pension from December 1833. The others were probably dead. Dates are from the 1838 Bengal Directory

- ↑ London Lancet, Volume 2 1859, (Google Books) page 354

- ↑ "The Medical Services of the British Army", The British and Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review or Quarterly Journal of Practical Medicine and Surgery, Vol XV, January-April 1855. The article starts on page 411, but the relevant pages are 444-447.

- ↑ "Supreme Government Orders 1869", page 36 from The Punjab Record or Reference Book for Civil Officers Volume 4 1869 Google Books

| This article was researched and prepared by Maureen Evers and Joss O’Kelly |